The role of laparoscopy in children with groin problems

The role of laparoscopy in children with groin problems

Minimally invasive surgery is an important advance in the development of modern surgery. There is an increasing trend to use laparoscopic techniques in pediatric urological practice for complex and reconstructive procedures on small children. In this review article, we focus on its benefits in diagnosis and management of various groin problems in children.

Undescended testis

Undescended testis is the most common congenital genitourinary anomaly in boys and has a prevalence of 1% to 9% in full term and 15% to 30% in premature male infants (1,2). Of all the undescended testis, 10-20% testes are non-palpable (1).

Pediatric laparoscopy dates back to 1976 when it was used, for the first time, for non-palpable testis (3). Since then laparoscopy has become one of the standards for both diagnosis as well as for the treatment of non-palpable testis (4-6). Diagnostic laparoscopy is commonly used for the assessment of a non-palpable testis, with the accuracy of testicular localization greater than 95% (7,8). Ultrasound, the most common non-invasive test performed, neither reliably localizes non-palpable testes nor does it rule out an intra-abdominal testis (1,9). Also, it does not alter the type of surgical approach in these patients and only adds to the health care expenditure (1,9,10). Diagnostic laparoscopy, compared to any imaging modality, has been shown to be more sensitive and specific for diagnosis and is helpful in assessment of the quality of the testis (1,6,11-13). In addition, many studies have shown various advantages of laparoscopy over open approaches including accurate identification of the presence or absence, viability, location, and the anatomy of the non-palpable testis (14-16). Interestingly, laparoscopy has also been demonstrated to have a beneficial role in establishing or refuting the diagnosis of an absent testis in previously inconclusive open exploration for a non-palpable testis (14,16-18). Additionally, it has been recently shown to help in the diagnosis of contralateral patent processus vaginalis in these patients; the incidence of which is around 20% (19,20).

Technique

Access to the peritoneal cavity

Two commonly used techniques are either an open or closed approach. For either, the stomach and the bladder should be emptied to avoid injury upon entering the abdomen. In addition, because the carbon dioxide used for insufflation is irritating, the patient should be either paralyzed or deeply anesthetized.

The open technique theoretically decreases the risk of iatrogenic injuries to the intra-abdominal structures, as well as reduces the risk of extra-peritoneal insufflations in inexperienced hands. In the open technique, a semi-lunar supra-umbilical or an infra-umbilical incision is used and is carried down to the rectus fascia. After sharply incising this layer, the pre-peritoneal fat is spread to expose the peritoneum. The peritoneum is grasped and opened sharply, followed by the placement of the trocar between the obliterated umbilical arteries. The size of the trocar is dependent on the size of the patient and varies from 2-3-mm to 5-mm and generally a zero-degree lens is used in most centers for pelvic laparoscopy (21). We prefer to use a closed technique of a Veress needle through the umbilicus followed by the dilation of the tract using a step system to allow for placement of a 2-3-mm trocar through the umbilicus (19,22). Pneumoperitoneum is achieved with carbon dioxide at a flow rate of 1 L/min (depending on the size of the child) at a maximum pressure of 15 mmHg; the pelvis is evaluated using a 0° 2.8-mm lens.

Diagnostic laparoscopy

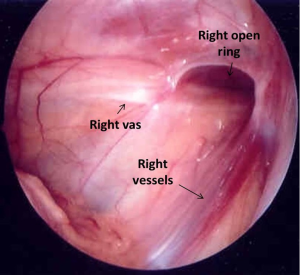

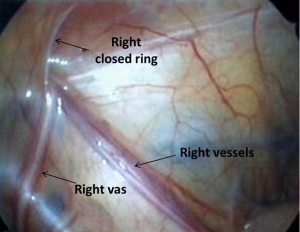

The midline pelvis is inspected for landmarks. Generally it is best to first identify the urinary bladder. Next, both obliterated umbilical arteries are identified. They run along the anterior abdominal wall, just lateral to the urinary bladder and serve an important anatomic land mark for identification of the internal ring, vas deferens, and ureter. The surgeon should next look laterally to locate the vas and vessels as they pass through the internal ring. The localization of these structures is best done on the contralateral normal side (in unilateral non-palpable testes) and can be confirmed by gentle traction on the testicle, during which the surgeon can see the cord structures slide beneath the peritoneum. Examining the contralateral normal side is useful for comparing normal anatomy, especially in the case of a vanishing testis, so that the thickness of the vessels can be compared directly. Additionally, it helps to identify a patent processus vaginalis on the contralateral normal side in a unilateral non-palpable testis (19,20). The testes can be classified into three groups according to their location detected during surgery: absent (vanishing testis syndrome), intra-abdominal, and inguinal (another frequently used term is canalicular).

Absent testis

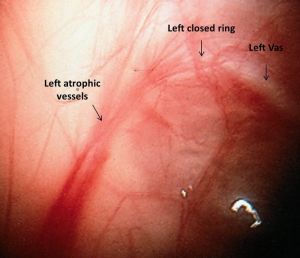

The finding of blind-ending vessels is pathognomonic for an absent testis and when, bilateral, has been termed vanishing testis syndrome. It is most commonly explained as in-utero torsion or a similar compromising vascular event. The spermatic vessels may be either normal or hypoplastic proximally (best to compare with the contralateral vessels), but distally as the vessels approach the internal ring they are atretic (Figure 1). This finding is seen in 36% to 64% patients with unilateral non-palpable testis (23-26). Several authors have suggested that compensatory hypertrophy of contralateral descended testis (26) with testicular length exceeding 2 cm indicates a vanishing testis. However, in our experience, this is not often seen and it is rarely convincing enough to avoid laparoscopy (27). A vanishing testis can be an intra-abdominal or inguinal-scrotal event (28). In an inguinal/scrotal vanishing testis the vas and atretic spermatic vessels can be dissected to the atrophic testicular remnant. It is controversial whether to remove the remnant (as about 10% of specimens reveal some residual germ cells) (29) and similarly controversial, some authors have recommended orchiopexy of the contralateral normal testis due to the presence of bilateral risk of torsion (24). In some cases, although a blind-ending vas is seen, blind-ending vessels are not noted in the vicinity. In these cases, the laparoscopic exploration must be carried in a rostral direction, accomplished by reflecting the bowel from the lateral gutter. Because there can be complete separation of the vas and testis, the exploration must visualize the spermatic vessels to be considered complete (30). When the spermatic vessels and vas enter the internal ring, one must consider the presence of viable testicular elements within the caudad extent of descent to rule out the possibility of testicular remnants or testicular nubbin (31,32). Histological hallmarks of an atrophic testicular remnant include fibrosis, hemosiderin deposition and calcification (29,32). In these patients, some clinicians would suggest that no further exploration is required as only 10-13% tissues have identifiable testicular tissues (33,34) while others recommend removal of these remnants due to potential risk of future malignant transformation (31,32,35). Due to the absence of long term follow up studies there are limited data available. If they are to be removed, the testicular remnants usually can be easily dissected through a scrotal or very low inguinal incision (31). We routinely recommend removal of these remnants and fixation of the contralateral testis as the patient is already under anesthesia.

Intra-abdominal testis

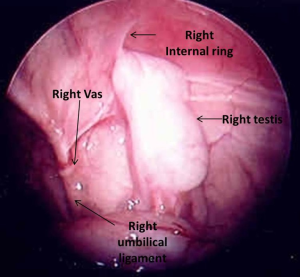

Intra-abdominal testes (Figure 2) are located inside the internal ring and considered either low (within 2 cm of the internal ring) or high (>2 cm from the internal ring) (36). Some authors have classified low intra-abdominal testis as lying between the internal ring and iliac vessels and high intra-abdominal testis as lying above the iliac vessels (37). The processus vaginalis is patent in most of the cases of low-lying testes and a long looping vas deferens can often be seen entering the internal ring. Elder in 1994 reported that an ipsilateral patent processus vaginalis is associated with 91% chance of finding a viable testis whereas if it was closed 97% had absent or vanished testis (25). However, since then, it has been clear that most high lying intra-abdominal testes are associated with a closed internal ring.

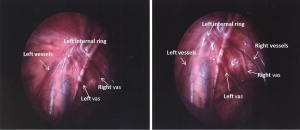

In some cases, no obvious testis or cord structures can be found following routine inspection. Sometimes the vessels are found medially deep in the pelvis with the testis lying alongside the bladder. If not, the exploration must be extended rostrally. The surgeon can reflect the colon by dividing along the line of Toldt and carrying the exploration to the level of the kidneys. In most instances, these maneuvers will allow discovery of the testis. In exceedingly rare circumstances, the testis has been found to be in perinephric, perihepatic location, or fused with spleen (38). Also a contralateral pelvic inspection should always be done to rule out ectopic testis (Figure 3) or remnant. These testes or testicular remnants can be dissociated from the vas/epididymis and vas/epididymal stump and may be mistaken for an absent testis. It is essential to search for the spermatic vessels vs. the vas deferens, as the testis may be lying proximate to the vessels and not necessarily proximate to the vas (30,32).

Inguinal or canalicular testis

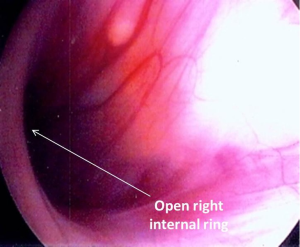

The surgeon can encounter an open internal inguinal ring with spermatic vessels entering the ring. In this case, the testis (or remnant) must be in the groin (31,37). In the case of some testes, gentle inguinal pressure will pop the testicle back into the abdomen. In either circumstance, the best treatment in most cases is a groin exploration (25).

Complications

Diagnostic laparoscopy is the most accurate means of determining whether a testis is intra-abdominal and has been shown to be a safe procedure in experienced hands (39,40). In a study by Passerotti et al., overall, there was a 2% complication rate, with 1.6% related to the access. Use of the Veress needle had a higher percentage of injuries compared to the open technique however the difference was not statistically significant. Other complications included pre-peritoneal insufflation sufficient to necessitate conversion to an open procedure (0.7%), vessel injury (0.4%), small bowel injury (0.4%), bleeding requiring conversion to open (0.1%), bladder perforation (0.1%) and vas deferens injury (0.2%) (40). The incidence of port site hernia after pediatric urological laparoscopy has been reported to be around 3.2%, similar to the reported incidence in adults and it is more likely to occur in infants (39).

Operative laparoscopy: laparoscopic orchiopexy/orchiectomy in non-palpable testis

Laparoscopic orchiopexy is now being done by many urologists for the management of an intra-abdominal testis. The author (BAK) is credited with performing one of the first laparoscopic orchiopexies in 1991 (41). Since then multiple studies have been done to compare the success rate of laparoscopic orchiopexy to open orchiopexy. Some of the initial studies reported a significant high number of Fowler-Stephens repairs instead of standard orchiopexy, probably due to a lack of standards for assessment of the length of the internal spermatic vessel pedicle (42). The length of the spermatic vessels is usually the limiting factor in tension-free mobilization of an intra-abdominal testis. One of the principal benefits of laparoscopic orchiopexy is that it allows access to the entire course of the spermatic vessels. Along with the magnification seen with laparoscopic approaches, the laparoscopic approach should aid in dissection and preservation of the main and collateral blood supply (43). Despite this, there are differences in the results, with early series of single-stage Fowler-Stephens laparoscopic orchiopexy showing a significantly higher atrophy of the testis than the two-stage repair and open approaches. But when comparing the two staged Fowler-Stephens approach, the laparoscopic approach had greater success than previously reported for the open approaches (44,45) and patients with a history of prior surgery had a higher risk of developing testicular atrophy (46). A meta-analysis and more recent studies have concluded that laparoscopic orchiopexy has a higher success rate as compared to open orchiopexy and it is, if not the procedure of choice, an acceptable and highly successful approach to the non-palpable undescended testis (44,46).

In a patient with low lying intra-abdominal testis laparoscopic orchiopexy can be performed with a relative ease (41). After the diagnostic laparoscopy, as described above, if it has been determined to proceed with laparoscopic orchiopexy, two 3 mm ports can be placed under direct laparoscopic vision. In recent years, we have placed the accessory instruments by incision alone, without using ports, to save expense, improve cosmesis and to reduce the risk of port site hernias. In a bigger child the other two ports can be placed in the mid-clavicular line, usually opposing each other at the level of the umbilicus. In infants, the ports must be placed high and laterally so that there is adequate working room in the tiny abdomen. Recently some authors have reported laparoscopic orchiopexy using single-incision multiport technique, however, long-term follow-up is required to fully evaluate its benefits and limitations (47).

The initial dissection begins by taking down the gubernaculum or other distal attachments of the testis. This is done sharply inside or at the internal ring while being careful to not damage the vas deferens or epididymis, especially keeping in mind of the possibility of long looping vas and the collateral blood supply of the testis. The peritoneum is incised sharply at the level of the internal ring lateral to the spermatic vessels up to the abdominal sidewall/psoas muscle and carried towards the origin of the vessels. Similarly the peritoneum is dissected medially from above downwards with direct visualization of the vas deferens. A large triangular window is left between the vessels and the vas. Preserving the peritoneum between the spermatic vessels and the vas is important for a two stage Stephen-Fowler orchiopexy, so as to preserve the collateral circulation to the testis. Even in a single stage procedure where the spermatic vessels are left intact, we attempt to preserve these collaterals. Further mobilization of the spermatic vessels, if required, can be done by dissecting the peritoneum away from the spermatic vessels and carrying the dissection of the spermatic vessels up to the level of the kidney. A subdartos pouch is created in a manner described for open orchiopexy (47). Delivery of the testis to the scrotum can be done by passing a curved hemostat (or large laparoscopic port) from the subdartos pouch over the symphysis pubis into the peritoneal cavity. This should be done, under direct vision, medial to the obliterated umbilical artery in order to shorten the distance to the scrotum (a version of the Prentiss maneuver). As in all orchiopexies, it is important to avoid excess tension on the spermatic cord but merely placing the testis in the scrotum allows for easier higher dissection of the vessels if needed. The testis is then placed within the dartos pouch. Before port removal, bleeding should be assessed laparoscopically, under low intra-abdominal pressure by releasing the pneumo-peritoneum. The fascia is closed with absorbable sutures in all port sites.

In the case of a high lying intra-abdominal testis the length of spermatic vessels is usually the limiting factor. In these patients a Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy is often the best option. The Fowler-Stephens procedure can be either a single-stage orchiopexy with division of the spermatic vessels (48) or a staged orchiopexy with division of the vessels at the first stage and testicle left in situ, followed by the second stage in 6 months (49). There are no absolute criteria for when division of spermatic vessels needs to be performed. It is easier to bring down testes in younger, smaller patients, but even in infants, a testis more than 2-3 cm away from the internal ring often requires either two stages or a division of the spermatic vessels (50,51). In a study by Koff et al. in 1996 there was no advantage of a two staged vs. a single stage Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy (52). However, in a recent meta-analysis it was shown that the two-staged Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy appears to carry a slightly higher rate of success than the single stage approach (85% versus 80% respectively) (53). During stage one, the spermatic vessels are cauterized or clipped, in situ, 2 to 3 cm superior to the intra-abdominal testis (51). The second stage of the orchiopexy is usually completed 3-6 months later. It can be performed in either open or in a laparoscopic fashion (54). In a laparoscopic technique, access to peritoneal cavity is obtained in a standard manner as described above. The same wide triangular peritoneal pedicle between the spermatic vessels and the vas is preserved. Dissection is restricted to the area medial to the vas and lateral to the vessels. Any gubernacular remnant is divided at the internal ring, and then the entire flap is dissected medial to the umbilical ligament care being taken to be at least 1 cm from the vas deferens. At this point the testis remains vascularized based on the peritoneal flap which is in turn based on the vas deferens. The testis is mobilized on this wide triangular peritoneum while carefully preserving the vasal artery and any collateral vasculature and placed in the subdartos pouch in a method described above (54).

Laparoscopic orchiectomy

Laparoscopic orchiectomy is done if the intra-abdominal testis is atrophic or hypoplastic. The vas can be clipped or divided with electrocautery, followed by ligation of the spermatic vessels and any gubernacular attachments. In most cases, testis being removed is small and can be delivered outside abdomen through a stretched 3 or 5-mm port (30).

Complications of laparoscopic orchiopexy

Results of open vs. laparoscopic orchiopexy procedures (primary or staged) are fairly comparable. However, laparoscopy has significantly less morbidity (37). Immediate complications of laparoscopic orchiopexy include mild ileus (41), ilioinguinal nerve injury and testicular torsion (55). Long term complications, as in the open procedure, can be testicular retraction (37) and testicular atrophy (36,37,54). Devascularization with atrophy of the testis can result from over-skeletonization of the cord, from overzealous use of electrocautery, from torsion of the spermatic vessels during passage of the testis into the scrotum, or as a result of ligation and division of the spermatic vessels during Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy (36,37,54). A long looping vas, though theoretically a benefit, has been reported to be associated with higher chances of testicular atrophy after laparoscopic orchiopexy (56).

Contralateral patent processus vaginalis

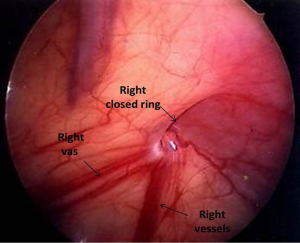

An additional benefit of diagnostic laparoscopy in unilateral non-palpable testis, has been in the diagnosis of contralateral patent processus vaginalis (Figures 4,5), the incidence of which has been around 10-20% (19,20,57). This rate is substantial and may pose a risk of developing a clinically significant inguinal hernia in the future. If a significant contralateral patent processus is found, this can be repaired easily at the same time of orchiopexy.

Although some authors have used a laparoscopic approach in the management of palpable testis (58,59), inguinal approaches have been the standard practice for palpable testes (60). However, the real benefit of laparoscopy, in these patients, is in the diagnosis of contralateral patent processus vaginalis. The rate of a contralateral patent processus vaginalis has been as high as 34% in those with an ipsilateral hernia sac. After considering age, side, prematurity, location, and volume of the undescended testis, boys with a testis distal to the external ring had three times higher odds of a patent contralateral processus vaginalis than those with testes lying within the inguinal canal (61). This is comparable to the patency rate of the contralateral processus vaginalis in patients undergoing repair of unilateral inguinal hernia, which ranges from 11-74% (62-68). Though the significance of this is unclear, it is likely associated with testicular ascent of previously descended or retractile testes.

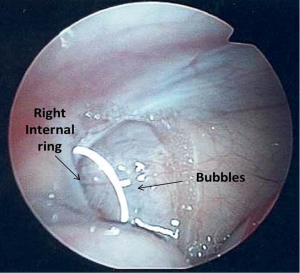

The presence of contralateral patent processus vaginalis in children presenting with a unilateral palpable testis can be safely and effectively evaluated by CO2 insufflation (Goldstein test) (69), trans-abdominal laparoscopy (70) or trans-inguinal laparoscopy (62,63,71) similar to as described for unilateral inguinal hernia repair. We prefer trans-inguinal approach. Orchiopexy is performed using an inguinal incision. After localization of the testis, a careful dissection of the ipsilateral hernia sac, if present, is done from the cord structures. The hernia sac is dissected sufficiently to allow full mobilization of the testis. For the initial few patients we used the CO2 insufflation test which is a modification of the Goldstein test (69) to determine the presence or absence of a contralateral patent processus vaginalis. The test is performed by introducing an 8 Fr feeding tube through the ipsilateral hernia sac into the abdominal cavity and distending the peritoneal cavity with CO2. The contra-lateral groin and the scrotum are then palpated for crepitance. The presence of crepitance constitutes a positive test result. Currently, we perform trans-inguinal laparoscopy involving both introduction of the 8Fr feeding tube and a 70° adult cystoscope lens. Carbon dioxide insufflation is accomplished at a flow rate of 1 L/min to a maximum pressure of 15 mmHg. The contralateral internal ring is visualized and inspected to determine patency (Figures 6,7). In cases where the patency is unclear, the contralateral inguinal canal and scrotum are palpated for evidence of crepitance and the internal ring is inspected for air bubbles after pressure on the contralateral inguinal area, a sign that CO2 had entered the groin (Figure 8). A contralateral patent processus can be repaired either with an open inguinal approach or there are a number of laparoscopic approaches described. In the absence of long term follow up studies it is not possible to estimate the impact of finding contralateral patent processus vaginalis. Potential advantages of examining the contralateral groin and closing a patent processus include avoiding a second anesthetic, sparing the parents the anxiety associated with a second operation, and sparing the physician the embarrassment associated with the appearance of a second hernia at a later date (71). In addition, we believe that a contralateral patent processus is associated with a contralateral “ascended” testis. Alternatively, finding the contralateral patent internal ring may lead to overtreatment of these patients as the true incidence of clinical significant contralateral hernia in these patients is not known.

Inguinal hernia

The basic principle of open inguinal hernia repair in pediatric patients is the ligation of the patent processus vaginalis and this is considered the gold standard for pediatric inguinal hernia repair (72-74). With the advent of the laparoscopic era, the trend began to move toward the application of laparoscopic techniques for pediatric hernia repair. In laparoscopic hernia repair, after the identification of patent internal ring, the overlying peritoneum is closed with a laparoscopic purse-string suture (75). The reported recurrence rate for pediatric laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair was approximately 4.4% (76,77) while the recurrence rate for open hernia repair has historically ranged from 0.3% to 2.5% (73,78,79). In order to improve these results, modifications and technical refinements of laparoscopic repair have been proposed, including placement of the stitch medial to the inferior epigastric artery (80) and the use of special needles or non-absorbable sutures (81). In addition, there are some very innovative techniques including a completely extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair (73) and laparoscopic hernia repair by the hook method (82) both of which have claimed a very low rate of recurrence in short follow up. Some studies have also reported that laparoscopic hernia repair in pediatric population leads to less pain, quicker recovery and better wound cosmesis. There is also the potential side benefit of simultaneous detection and repair of contralateral patent processus vaginalis (75,83,84). However the very low morbidity of open pediatric inguinal hernia repair with its proven long-term efficacy and low rate of damage to the vas, suggests that long term follow up studies are needed before laparoscopic hernia repair will replace the open inguinal hernia repair in pediatric patients (75,84).

Contralateral patent processus vaginalis

Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of laparoscopic inguinal repair over open hernia repair in pediatric patients, the role of diagnostic laparoscopy for detection of contralateral patent processus vaginalis in patients with unilateral inguinal should not be underestimated (85-88). A meta-analysis reported that diagnostic laparoscopy is 99.4% sensitive and 99.5% specific in identifying the presence of a contralateral patent processus vaginalis (89). The reported patency rate of a contralateral patent processus vaginalis in patients with unilateral inguinal hernia has ranges widely from 11-74% amongst different studies (62-68,90). Whether the contralateral groin should be examined is a matter of debate with the authors of many publications taking sides in this debate. The opponents of routine contralateral groin exploration argue that it may lead to overtreatment of patients, as the true incidence of clinically significant contralateral hernia is only 5-29% (91-94) hence they argue that the repair of a contralateral processus vaginalis should not be performed (95-97). On the other hand, other authors have recommended the routine inspection as well as repair of contralateral patent processus vaginalis, as it is safe, reproducible, technically easy (20,86,98) and cost effective (99). Also, there are the advantages of avoidance of a second anesthetic, sparing the parents of the anxiety associated with a second operation, and sparing the physician the embarrassment associated with the appearance of a second hernia at a later date (71). For these above mentioned reasons we routinely inspect and repair contralateral patent processus vaginalis.

The presence of a contralateral patent processus vaginalis in children with unilateral inguinal hernia can be safely and effectively evaluated by CO2 insufflation (Goldstein test) (69), transabdominal laparoscopy (70) or transinguinal laparoscopy (62,63,71). We prefer transinguinal laparoscopic approach in our center as described above in section of palpable testis.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Tasian GE, Copp HL. Diagnostic performance of ultrasound in nonpalpable cryptorchidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011;127:119-28. [PubMed]

- Boisen KA, Kaleva M, Main KM, et al. Difference in prevalence of congenital cryptorchidism in infants between two Nordic countries. Lancet 2004;363:1264-9. [PubMed]

- Cortesi N, Ferrari P, Zambarda E, et al. Diagnosis of bilateral abdominal cryptorchidism by laparoscopy. Endoscopy 1976;8:33-4. [PubMed]

- Fahlenkamp D, Rassweiler J, Fornara P, et al. Complications of laparoscopic procedures in urology: experience with 2,407 procedures at 4 German centers. J Urol 1999;162:765-70. [PubMed]

- Gapany C, Frey P, Cachat F, et al. Management of cryptorchidism in children: guidelines. Swiss Med Wkly 2008;138:492-8. [PubMed]

- Gatti JM, Ostlie DJ. The use of laparoscopy in the management of nonpalpable undescended testes. Curr Opin Pediatr 2007;19:349-53. [PubMed]

- Moore RG, Peters CA, Bauer SB, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation of the nonpalpable tests: a prospective assessment of accuracy. J Urol 1994;151:728-31. [PubMed]

- Tennenbaum SY, Lerner SE, McAleer IM, et al. Preoperative laparoscopic localization of the nonpalpable testis: a critical analysis of a 10-year experience. J Urol 1994;151:732-4. [PubMed]

- Hrebinko RL, Bellinger MF. The limited role of imaging techniques in managing children with undescended testes. J Urol 1993;150:458-60. [PubMed]

- Elder JS. Ultrasonography is unnecessary in evaluating boys with a nonpalpable testis. Pediatrics 2002;110:748-51. [PubMed]

- Elder JS. Laparoscopy and Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy in the management of the impalpable testis. Urol Clin North Am 1989;16:399-411. [PubMed]

- Bellinger MF. The blind-ending vas: the fate of the contralateral testis. J Urol 1985;133:644-5. [PubMed]

- Bakr AA, Kotb M. Laparoscopic orchidopexy: the treatment of choice for the impalpable undescended testis. JSLS 1998;2:259-62. [PubMed]

- Diamond DA, Caldamone AA. The value of laparoscopy for 106 impalpable testes relative to clinical presentation. J Urol 1992;148:632-4. [PubMed]

- Boddy SA, Corkery JJ, Gornall P. The place of laparoscopy in the management of the impalpable testis. Br J Surg 1985;72:918-9. [PubMed]

- Barqawi AZ, Blyth B, Jordan GH, et al. Role of laparoscopy in patients with previous negative exploration for impalpable testis. Urology 2003;61:1234-7. [PubMed]

- Diamond DA, Caldamone AA. The value of laparoscopy for 106 impalpable testes relative to clinical presentation. J Urol 1992;148:632-4. [PubMed]

- Lakhoo K, Thomas DF, Najmaldin AS. Is inguinal exploration for the impalpable testis an outdated operation? Br J Urol 1996;77:452-4. [PubMed]

- Onal B, Kogan BA. Additional benefit of laparoscopy for nonpalpable testes: finding a contralateral patent processus. Urology 2008;71:1059-63. [PubMed]

- Palmer LS, Rastinehad A. Incidence and concurrent laparoscopic repair of intra-abdominal testis and contralateral patent processus vaginalis. Urology 2008;72:297-9. [PubMed]

- Humke U, Siemer S, Bonnet L, et al. Pediatric laparoscopy for nonpalpable testes with new miniaturized instruments. J Endourol 1998;12:445-50. [PubMed]

- Brown RA, Millar AJ, Jee LD, et al. The value of laparoscopy for impalpable testes. S Afr J Surg 1997;35:70-3. [PubMed]

- Wilson-Storey D, MacKinnon AE. The laparoscope and the undescended testis. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:89-92. [PubMed]

- Rappe BJ, Zandberg AR, De Vries JD, et al. The value of laparoscopy in the management of the impalpable cryptorchid testis. Eur Urol 1992;21:164-7. [PubMed]

- Elder JS. Laparoscopy for impalpable testes: significance of the patent processus vaginalis. J Urol 1994;152:776-8. [PubMed]

- Huff DS, Snyder HM 3rd, Hadziselimovic F, et al. An absent testis is associated with contralateral testicular hypertrophy. J Urol 1992;148:627-8. [PubMed]

- Koff SA. Does compensatory testicular enlargement predict monorchism? J Urol 1991;146:632-3. [PubMed]

- Van Savage JG. Avoidance of inguinal incision in laparoscopically confirmed vanishing testis syndrome. J Urol 2001;166:1421-4. [PubMed]

- Cendron M, Schned AR, Ellsworth PI. Histological evaluation of the testicular nubbin in the vanishing testis syndrome. J Urol 1998;160:1161-2. [PubMed]

- Jordan GH. Laparoscopic management of the undescended testicle. Urol Clin North Am 2001;28:23-29. vii-viii. [PubMed]

- Plotzker ED, Rushton HG, Belman AB, et al. Laparoscopy for nonpalpable testes in childhood: is inguinal exploration also necessary when vas and vessels exit the inguinal ring? J Urol 1992;148:635-7. [PubMed]

- De Luna AM, Ortenberg J, Craver RD. Exploration for testicular remnants: implications of residual seminiferous tubules and crossed testicular ectopia. J Urol 2003;169:1486-9. [PubMed]

- Hegarty PK, Mushtaq I, Sebire NJ. Natural history of testicular regression syndrome and consequences for clinical management. J Pediatr Urol 2007;3:206-8. [PubMed]

- Grady RW, Mitchell ME, Carr MC. Laparoscopic and histologic evaluation of the inguinal vanishing testis. Urology 1998;52:866-9. [PubMed]

- Storm D, Redden T, Aguiar M, et al. Histologic evaluation of the testicular remnant associated with the vanishing testes syndrome: is surgical management necessary? Urology 2007;70:1204-6. [PubMed]

- El-Anany F, Gad El-Moula M, Abdel Moneim A, et al. Laparoscopy for impalpable testis: classification-based management. Surg Endosc 2007;21:449-54. [PubMed]

- Abolyosr A. Laparoscopic versus open orchiopexy in the management of abdominal testis: a descriptive study. Int J Urol 2006;13:1421-4. [PubMed]

- Argos Rodriguez MD, Unda Freire A, Ruiz Orpez A, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for nonpalpable testis. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1756-8. [PubMed]

- Cost NG, Lee J, Snodgrass WT, et al. Hernia after pediatric urological laparoscopy. J Urol 2010;183:1163-7. [PubMed]

- Passerotti CC, Nguyen HT, Retik AB, et al. Patterns and predictors of laparoscopic complications in pediatric urology: the role of ongoing surgical volume and access techniques. J Urol 2008;180:681-5. [PubMed]

- Bogaert GA, Kogan BA, Mevorach RA. Therapeutic laparoscopy for intra-abdominal testes. Urology 1993;42:182-8. [PubMed]

- Ferro F, Lais A, Gonzalez-Serva L. Benefits and afterthoughts of laparoscopy for the nonpalpable testis. J Urol 1996;156:795-8. [PubMed]

- Lindgren BW, Franco I, Blick S, et al. Laparoscopic Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy for the high abdominal testis. J Urol 1999;162:990-3. [PubMed]

- Baker LA, Docimo SG, Surer I, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of laparoscopic orchidopexy. BJU Int 2001;87:484-9. [PubMed]

- Lintula H, Kokki H, Eskelinen M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open orchidopexy in children with intra-abdominal testes. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2008;18:449-56. [PubMed]

- Chang B, Palmer LS, Franco I. Laparoscopic orchidopexy: a review of a large clinical series. BJU Int 2001;87:490-3. [PubMed]

- de Lima GR, da Silveira RA, de Cerqueira JB, et al. Single-incision multiport laparoscopic orchidopexy: initial report. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:2054-6. [PubMed]

- Fowler R, Stephens FD. The role of testicular vascular anatomy in the salvage of high undescended testes. Aust N Z J Surg 1959;29:92-106. [PubMed]

- Bloom DA. Two-step orchiopexy with pelviscopic clip ligation of the spermatic vessels. J Urol 1991;145:1030-3. [PubMed]

- Agrawal A, Joshi M, Mishra P, et al. Laparoscopic Stephen-Fowler stage procedure: appropriate management for high intra-abdominal testes. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2010;20:183-5. [PubMed]

- Elder JS. Two-stage Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy in the management of intra-abdominal testes. J Urol 1992;148:1239-41. [PubMed]

- Koff SA, Sethi PS. Treatment of high undescended testes by low spermatic vessel ligation: an alternative to the Fowler-Stephens technique. J Urol 1996;156:799-803. [PubMed]

- Elyas R, Guerra LA, Pike J, et al. Is staging beneficial for Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy? A systematic review. J Urol 2010;183:2012-8. [PubMed]

- Esposito C, Garipoli V. The value of 2-step laparoscopic Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy for intra-abdominal testes. J Urol 1997;158:1952-4; discussion 1954-5.

- de Vylder AM, Breeuwsma AJ, van Driel MF, et al. Torsion of the spermatic cord after orchiopexy. J Pediatr Urol 2006;2:497-9. [PubMed]

- Dave S, Manaboriboon N, Braga LH, et al. Open versus laparoscopic staged Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy: impact of long loop vas. J Urol 2009;182:2435-9. [PubMed]

- Weiss RM, Seashore JH. Laparoscopy in the management of the nonpalpable testis. J Urol 1987;138:382-4. [PubMed]

- He D, Lin T, Wei G, et al. Laparoscopic orchiopexy for treating inguinal canalicular palpable undescended testis. J Endourol 2008;22:1745-9. [PubMed]

- Riquelme M, Aranda A, Rodriguez C, et al. Laparoscopic orchiopexy for palpable undescended testes: a five-year experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2006;16:321-4. [PubMed]

- Körner I, Rübben H. Undescended testis: aspects of treatment. Urologe A 2010;49:1199-205; quiz 1206.

- Aggarwal H, Kogan BA, Feustel PJ. One third of patients with a unilateral palpable undescended testis have a contralateral patent processus. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:1711-5. [PubMed]

- DuBois JJ, Jenkins JR, Egan JC. Transinguinal laparoscopic examination of the contralateral groin in pediatric herniorrhaphy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1997;7:384-7. [PubMed]

- Holcomb GW 3rd, Morgan WM 3rd, Brock JW 3rd. Laparoscopic evaluation for contralateral patent processus vaginalis: Part II. J Pediatr Surg 1996;31:1170-3. [PubMed]

- Fuenfer MM, Pitts RM, Georgeson KE. Laparoscopic exploration of the contralateral groin in children: an improved technique. J Laparoendosc Surg 1996;6 Suppl 1:S1-4. [PubMed]

- Liu C, Chin T, Jan SE, et al. Intraoperative laparoscopic diagnosis of contralateral patent processus vaginalis in children with unilateral inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 1995;82:106-8. [PubMed]

- Wolf SA, Hopkins JW. Laparoscopic incidence of contralateral patent processus vaginalis in boys with clinical unilateral inguinal hernias. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29:1118-20. [PubMed]

- Duvie SO. The incidence of contralateral patent processus vaginalis in unilateral inguinal hernia in Nigerian children. Trop Geogr Med 1984;36:371-3. [PubMed]

- Watanabe T, Nakano M, Endo M. An investigation on the mechanism of contralateral manifestations after unilateral herniorrhaphy in children based on laparoscopic evaluation. J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:1543-7. [PubMed]

- Timberlake GA, Ochsner MG, Powell RW. Diagnostic pneumoperitoneum in the pediatric patient with a unilateral inguinal hernia. Arch Surg 1989;124:721-3. [PubMed]

- Holcomb GW 3rd, Brock JW 3rd, Morgan WM 3rd. Laparoscopic evaluation for a contralateral patent processus vaginalis. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29:970-3. [PubMed]

- Klin B, Efrati Y, Abu-Kishk I, et al. The contribution of intraoperative transinguinal laparoscopic examination of the contralateral side to the repair of inguinal hernias in children. World J Pediatr 2010;6:119-24. [PubMed]

- Potts WJ, Riker WL, Lewis JE. The treatment of inguinal hernia in infants and children. Ann Surg 1950;132:566-76. [PubMed]

- Endo M, Watanabe T, Nakano M, et al. Laparoscopic completely extraperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia in children: a single-institute experience with 1,257 repairs compared with cut-down herniorrhaphy. Surg Endosc 2009;23:1706-12. [PubMed]

- Levitt MA, Ferraraccio D, Arbesman MC, et al. Variability of inguinal hernia surgical technique: A survey of North American pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:745-51. [PubMed]

- Niyogi A, Tahim AS, Sherwood WJ, et al. A comparative study examining open inguinal herniotomy with and without hernioscopy to laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in a pediatric population. Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:387-92. [PubMed]

- Laberge JM. What's new in pediatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2002;195:208-18. [PubMed]

- Montupet P, Esposito C. Laparoscopic treatment of congenital inguinal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:420-3. [PubMed]

- Carneiro PM. Inguinal herniotomy in children. East Afr Med J 1990;67:359-64. [PubMed]

- Harvey MH, Johnstone MJ, Fossard DP. Inguinal herniotomy in children: a five year survey. Br J Surg 1985;72:485-7. [PubMed]

- Chan KL, Tam PK. Technical refinements in laparoscopic repair of childhood inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc 2004;18:957-60. [PubMed]

- Shalaby R, Ismail M, Dorgham A, et al. Laparoscopic hernia repair in infancy and childhood: evaluation of 2 different techniques. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:2210-6. [PubMed]

- Tam YH, Lee KH, Sihoe JD, et al. Laparoscopic hernia repair in children by the hook method: a single-center series of 433 consecutive patients. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:1502-5. [PubMed]

- Chan KL, Hui WC, Tam PK. Prospective randomized single-center, single-blind comparison of laparoscopic vs open repair of pediatric inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc 2005;19:927-32. [PubMed]

- Saranga Bharathi R, Arora M, Baskaran V. Pediatric inguinal hernia: laparoscopic versus open surgery. JSLS 2008;12:277-81. [PubMed]

- Valusek PA, Spilde TL, Ostlie DJ, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation for contralateral patent processus vaginalis in children with unilateral inguinal hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2006;16:650-3. [PubMed]

- Holcomb GW 3rd, Miller KA, Chaignaud BE, et al. The parental perspective regarding the contralateral inguinal region in a child with a known unilateral inguinal hernia. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:480-2. [PubMed]

- Nixon RG, Pope JC 4th, Adams MC, et al. Laparoscopic variability of the internal inguinal ring: review of anatomical variation in children with and without a patent processus vaginalis. J Urol 2002;167:1818-20. [PubMed]

- Holcomb GW 3rd. Diagnostic laparoscopy for congenital inguinal hernia. Semin Laparosc Surg 1998;5:55-9. [PubMed]

- Miltenburg DM, Nuchtern JG, Jaksic T, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation of the pediatric inguinal hernia--a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:874-9. [PubMed]

- Tackett LD, Breuer CK, Luks FI, et al. Incidence of contralateral inguinal hernia: a prospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34:684-7. [PubMed]

- Ron O, Eaton S, Pierro A. Systematic review of the risk of developing a metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia in children. Br J Surg 2007;94:804-11. [PubMed]

- Miltenburg DM, Nuchtern JG, Jaksic T, et al. Meta-analysis of the risk of metachronous hernia in infants and children. Am J Surg 1997;174:741-4. [PubMed]

- Surana R, Puri P. Is contralateral exploration necessary in infants with unilateral inguinal hernia? J Pediatr Surg 1993;28:1026-7. [PubMed]

- McGregor DB, Halverson K, McVay CB. The unilateral pediatric inguinal hernia: Should the contralateral side by explored? J Pediatr Surg 1980;15:313-7. [PubMed]

- Maddox MM, Smith DP. A long-term prospective analysis of pediatric unilateral inguinal hernias: should laparoscopy or anything else influence the management of the contralateral side? J Pediatr Urol 2008;4:141-5. [PubMed]

- Carneiro PM, Rwanyuma L. Occurrence of contralateral inguinal hernia in children following unilateral inguinal herniotomy. East Afr Med J 2004;81:574-6. [PubMed]

- Shabbir J, Moore A, O'Sullivan JB, et al. Contralateral groin exploration is not justified in infants with a unilateral inguinal hernia. Ir J Med Sci 2003;172:18-9. [PubMed]

- Mollen KP, Kane TD. Inguinal hernia: what we have learned from laparoscopic evaluation of the contralateral side. Curr Opin Pediatr 2007;19:344-8. [PubMed]

- Lee SL, Sydorak RM, Lau ST. Laparoscopic contralateral groin exploration: is it cost effective? J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:793-5. [PubMed]